Seeing thousands of folks of all colors and persuasions protesting against racial and judicial inequality is one of the most hopeful expressions of dissent that I’ve witnessed in 50 years. It also attests to the power of imagery. Today’s movement for equality is reminiscent of America in the 1950s and 1960s. In my memoir, “Sugar Hill Where the Sun Rose Over Harlem,(https://www.amazon.com/Sugar-Hill-Where-Rose-Harlem/dp/0984692908/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=sugar+hill+where+the+sun+rose+over+harlem&qid=1598321231&s=books&sr=1-1 I write about growing up in Harlem during the turbulent Civil Rights era. On Sugar Hill, where I was raised, almost every family had fled the South’s brutal and racist Jim Crow system.

On Sugar Hill, where I was raised, almost every family had fled the South’s brutal and racist Jim Crow system.s in the South, Sugar Hill, the legendary and idyllic Harlem neighborhood, had its own hierarchy. Those who had money and stature were said to have “Arrived.” Often they were intellectuals and professionals such as Thurgood Marshall or Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. But celebrities from humble roots also fit this category. People like Willie Mays, the New York Giants outfielder, jazz legend Ella Fitzgerald or, World Champion Boxer Joe Lewis were among the arrived.

The residents whose hard work was greatly responsible for Harlem’s development and character rarely got noticed. They cut hair in barbershops, eked out a living in mom and pop stores, worked in subway tollbooths, or like my mother, typed ads at the “Amsterdam News.” These were Sugar Hill “Strivers,” working class adults who clung perilously to the sweet life on Sugar Hill.

Not many of the “Poor” black people lived on Sugar Hill. Often, Harlem’s poorest residents were recent migrants from Georgia plantations, North Carolina tobacco farms, or citrus groves in Florida. They squeezed into cramped tenements among a horde of other relatives. Until they learned city ways, they existed on handouts or odd jobs around the neighborhood.

When it came right down to it, it didn’t matter where any of us fit into the hierarchy because we all had black skin, and Harlem was our safe zone. In Harlem, it was safe to rent an apartment, or buy a house (although both were usually at inflated prices) without being shamed or denied. The East Side, Upper West Side, or any of the Post-WWII bedroom communities being built in the suburbs were off limits to folks like us.

Although my family was more fortunate than many black people, in my book “Sugar Hill,” I write about the little indignities that infiltrated black life because of our skin color–even living in NYC 100 years after slavery’s end. As children, we weren’t always aware of these slights and affronts, because a first order of business for the adults who raised us on Sugar Hill was to protect us and build our self-esteem.

Yet by observing my quick-to-take-offense grandmother, and watching television, I quickly learned that the world was not always safe for people like us. But I was a young adult before I began to understand that Sugar Hill was the gift our parents gave us children, and they’d had no intention of tarnishing our lives with stories of personal humiliation and cruelty such as those witnessed on television.

During this era, two horrifying racist events occurred in the South (beyond the hundreds of black people being lynched) that finally caused people of all colors to sit up and pay attention. A fourteen year-old black boy, Emmett Till was abducted, tortured, then murdered in Mississippi. Newspaper and television viewers, along with his grieving mother, stared into the open casket at a once handsome young man’s face, now unrecognizable and grotesquely swollen from a savage beating.

In 1963, after Dr. King’s seminal “I Have a Dream” speech,” four Klansmen dynamited a Birmingham, Alabama church, killing four little black girls. Again, the media trained their cameras on a twelve year-old survivor’s swollen, bandaged face and her blinded eye.

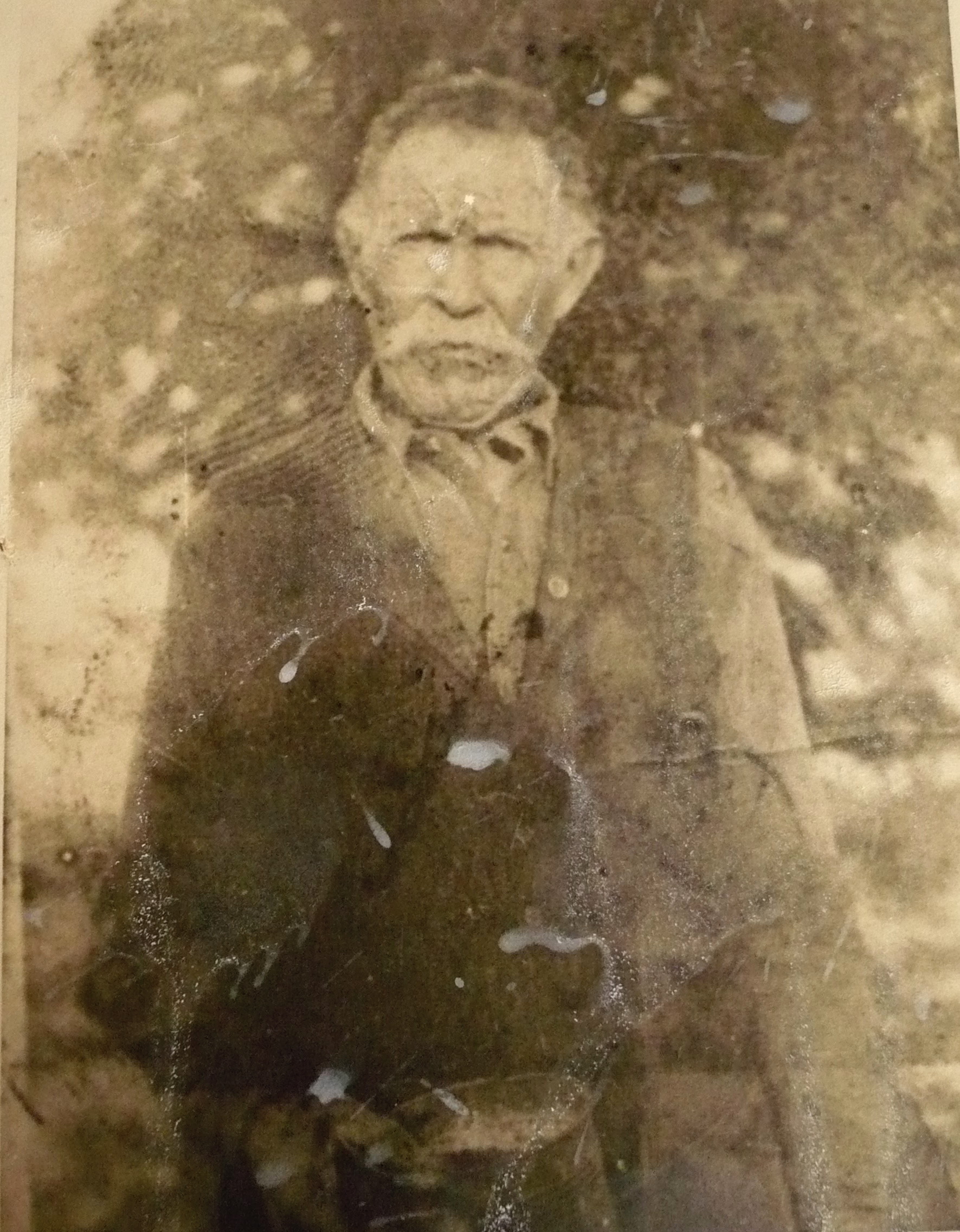

With continued violence, protests, boycotts, sit-ins, and more violence, Harlem got fired up, and the South was on fire over the entrenched Jim Crow, black/white-racial hierarchy. What endured then in the South was not so different from South Africa’s apartheid system. Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and author Isabel Wilkerson says today’s protest and our continued lack of equality is about ending an American caste system. Whether you call it slavery, Jim Crow, apartheid, a caste system, or age-old racism, it’s endemic and it’s been a part of America for too long (My great great grandfather, a former slave).

But I’m hopeful because the demand for racial equality is resonating. This time more ears are listening, and all eyes have seen a black man named George Floyd pinned under the knees of a seemingly indifferent white police officer, while Floyd pleaded for his life and repeatedly said, “I can’t breathe.” In less than an hour he was dead.

The loud opposition who considers itself the head honchos of our hierarchy remains vocal. At this point in history, however, their idea of America is not working well. I’m hopeful because what those noisy nonbelievers keep shouting is clashing with the truth of what our eyes cannot deny.