In 2004, tourists in Havana were commonly accosted by a local who, to earn extra money, tried to steer them to certain businesses. The guy who zeroed-in on us was Michel, a 24 year-old who did not appear threatening, and promised he wasn’t selling anything. So, we listened to his pitch.

Michel pointed to a rundown, but charming old Colonial building with an outside staircase leading up to a paladar—a second floor apartment restaurant, belonging to a family who prepared meals for tourists. I later learned that these paladares were often illegal. After observing several older people slowly walk up and down the stairs, we agreed to take a peek.

In her dining room—a 1950s-style kitchen—a matronly Señora looked eager to feed us. A home cooked Cuban meal was tempting, but would take a long time. That evening, the famous Bueno Vista Social Club band was playing. I’d recently seen their 1999 documentary of the same name and really wanted to hear them, so we politely declined.

Once back on the street, a security guy suddenly walked up, grabbed Michel, acted tough and scary, but slightly undecided about what to do to him, before letting go and saying something in Spanish. All of us were unnerved. I assumed Michel was targeted for being with us and for coming out of the paladar. I thought it best to say goodbye, but thanked and tipped him since we had enjoyed his company. These obvious security “watchers” were all around the streets, and outside our hotel, eyeballing all who entered, which seemed to be only foreigners. Uniformed policemen also patrolled in cars, but they looked like regular cops.

The concert that night was jammed—with foreigners. The band mostly played classic pre-revolutionary Cuban music, with some original band members up on stage jamming with the younger guys. Other old timers walked around greeting guests.

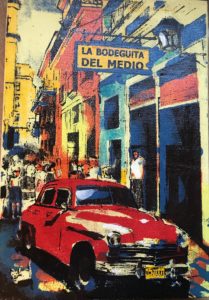

The next morning, Henny and I discovered an outdoor craft market where I bought a tiny oil painting (below) with the last of my cash. Next, we rushed around the Museo Bella Arte, a gorgeous modern museum, then hurried back to the hotel. Unfortunately, we were six minutes late and our room keycards didn’t work. I tried not to panic, but imaged a worse case scenario in trying to get off that island. We had neither cell phones (a rarity then) nor money, as all transactions had been in cash. US credit cards didn’t work in Cuba.

Back at the desk, the clerk looked infuriatingly smug, as I breathlessly explained our situation, which she knew only too well. “The signs in English clearly state…” she said, but then made a call. She listened, looked at me strangely, then hung up as I held my breath. After what seemed like forever, she finally spoke. “Okay, you can go up and get your luggage.” I knew immediately it was the $1.00.

That morning, I left a tip for the maid, which I usually don’t do when leaving. My logic is probably flawed, but I figure I should only tip when I’m staying over. That way, the maid cleans up just for me, and I thank her.

But, the day before while chatting with a Canadian, a young woman with a toddler on her hip had walked up and asked me for money, and I shook my head, no. The Canadian got very agitated. “Oh, no.” she said. “These women are desperately poor. If you could, you should have given her something.” That bothered me for the rest of the trip, so, no way was I not going to tip the maid—another young woman who might also have a young child.

I hope that $1.00 made a difference to her, but I know it’s kept me out of a heap of trouble.

To be continued